Strategies for Building a Sustainable Arthouse Cinema in Europe

What is the CresCine Project?

This guide is produced in the framework of CresCine, a Horizon Europe-funded project aimed at boosting the international competitiveness and cultural diversity of the European film industry, with a particular focus on small markets.

Running from 1 March 2023 to 28 February 2026, this 36-month initiative is part of a broader EU effort to enhance the global presence of European filmmaking, alongside two other Horizon-funded projects: SCENE, which integrates cutting-edge technology with sustainability and social responsibility, and REBOOT, focusing on youth engagement and VOD platform development.

The main objective of CresCine is to transform small European film markets by developing targeted research, conducting pilot projects, and generating actionable insights that can drive the sector's growth. The project’s scope covers a wide range of key areas: the overall state of the market, audience analysis, sustainability (greening), skills development, distribution and exhibition, as well as financing and innovation.

Through collaboration with over 28 academic and industry organisations—ranging from academic researchers to influential industry players—CresCine will produce State of the Industry reports, detailed datasets, and strategic recommendations. Additionally, the project will host industry sessions at major film festivals, providing valuable platforms to discuss findings and drive forward policy and market innovation.

By piloting its research outcomes in seven European markets, CresCine seeks to empower small markets, enhance their global competitiveness, and contribute to the diversity of cinema in Estonia, Lithuania, Denmark, Ireland, Belgium (Flanders), Croatia, and Portugal.

Work Package 6 objectives

This study is part of Work Package 6 (WP6) of CresCine. The WP6 focuses on the critical challenges faced by the distribution, exhibition, and marketing sectors in small European film markets.

The WP6 aims to:

Generate new knowledge on the specific needs of the distribution, exhibition, and marketing sub-sectors.

Strengthen distribution, exhibition, and marketing strategies in small EU markets.

Enhance the global reach and visibility of content originating from these markets.

Co-Authors

Statement of Originality

This deliverable contains original unpublished work except where clearly indicated otherwise. Acknowledgement of previously published material and of the work of others has been made through appropriate citation, quotation, or both.

Disclaimer

The European Commission’s support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

This study presents a case study of Lumière Mechelen, a project that demonstrates the importance of creating the right context for cinema, securing government support, building a strong network of business and cultural partners, and developing a clear and distinct strategy for the position of city screens within a broader landscape of exhibitors. It also highlights the significance of cultural entrepreneurship.

Ten essentials for a viable and high-quality city cinema, according to Lumière:

The appropriate sense of cultural entrepreneurship to make possible what is difficult.

A meaningful and generous partnership with a city.

A strong relationship with a bank.

A remarkable and inspiring building and a talented architect. A robust technical infrastructure.

An inviting café next to the cinema to upgrade film-going into an evening out experience.

An impactful program, curated with a broad mindset and sound judgment.

A solid business plan, including a clever, efficient, and effective HR concept.

A cinema that plays an integral role in the film industry’s value chain.

A cinema linked to other cinemas of the same brand, cinemas that have the same mission and conviction, so that investment, energy, and determination can be shared.

A cinema in touch with its audience, consciously using the right audience strategy.

Two aspects are crucial:

Firstly, what sets a Lumière cinema apart from a fully commercial one is its foundation in cultural entrepreneurship—a shared yet diversely interpreted approach that shapes its distinct identity. Cultural entrepreneurship is the skill and talent required to make this added value economically viable, even though, at first glance, it may seem to contradict purely economic logic. It is noteworthy that all the key partners in the project refer to this same concept to define their vision*:

The architect aims to build more than just a structure; he envisions a building that fosters positive social dynamics.

The city seeks more than just a cinema; it leverages a historic building and the cinema itself to enhance the urban landscape and create new social interactions.

Triodos Bank only finances projects that have a social, cultural, or environmental impact.

‘Het Anker’ explicitly states that, as a city brewery, this project represents more than just profitability—it carries a deeper purpose.

Maintaining or developing viable venues for theatrical release is costly and requires significant investment, with venue and infrastructure costs playing a key role. The case of Cinema Lumière Mechelen highlights the value of policy support at both local and regional levels. Supporting city cinemas should be recognised as an integral part of urban development, helping to create the right conditions for cities to offer a vibrant, accessible, and diverse cultural experience for a wide range of residents. Investment in venues and infrastructure is essential, but it must also be accompanied by thoughtful planning around public space, transport, and the night-time economy (such as bars, restaurants, and other leisure activities).

Key Management Insights

* See also Europa Cinemas (2023). Europa Cinemas Network survey. URL: https://www.europa-cinemas.org/storage/press_file/70/file_src/97bbc069b22d81e0f68852ae8513b964.pdf; Koljonen, J. (2024). Nostradamus 2024: a paradox of hope. Göteborg: Göteborg Film Festival;Raats, T., Biltereyst, D., Meers, P., Van de Wouwer, S. & Asmar, A. (2024). Analyse van filmexploitatie in Vlaanderen. Studie in opdracht van het Vlaams Audiovisueel Fonds. Available at: https://www.vaf.be/files/Publiekswerking/documenten/Analyse-van-Filmexploitatie-in-Vlaanderen_def.pdf

Introduction

Contextualising current challenges for theatrical exhibitors in Europe

The landscape of theatrical exhibitors in Europe includes multiplexes, cityplexes, arthouse cinemas, small-profit cinemas, and various cultural venues. Each plays its own role, contributing to a diverse and complementary patchwork of cultural entrepreneurs. Since each type of exhibitor has a distinct function, they also face different challenges. Arthouse and smaller for-profit cinemas, in particular, are confronted with a series of unique obstacles.

Thanks to the continued demand for arthouse films and the fact that audience attendance has (significantly, but not entirely) recovered since the COVID-19 pandemic, many arthouse cinemas report that audience attendance or competition with streaming services are not their primary concerns. Studies have shown that for arthouse cinemas, economic downturns, inflation, and international conflicts have further intensified pressure on smaller cinemas. Cinemas report that (i) short-term operational costs, such as replacing first-generation digital projectors, (ii) the need for investment in making venues accessible and energy-efficient, and (iii) significantly increased staff costs, have placed substantial pressure on their economic viability.

The above calls for a comprehensive approach to maintain a viable and vibrant arthouse and city cinema landscape. Part of this strategy involves transforming existing venues to meet evolving expectations, while another part focuses on creating and exploring new venues for cinema screens, particularly in regions with a relatively low number of screens per capita, such as Belgium.

The Cinema Lumière Mechelen (Lumière Mechelen) case study confirms the importance of creating the right contextual conditions for both existing and new theatrical venues to thrive. Studies have highlighted the importance of (i) location and proximity, with easy access to public transport, (ii) investing in the right cinematic experience, which for multiplexes often means state-of-the-art sound and image quality, while arthouse cinemas emphasise the importance of diverse events, festivals, educational screenings, and nearby dining or drinking options, (iii) the importance of target group-based and local marketing, supported by a data-driven audience strategy, and (iv) a distinct programming strategy that caters to multiple audiences.

Successful examples of creating the right circumstances highlight the importance of cultural entrepreneurship, as well as various direct and indirect forms of local government support. Municipalities that have successfully invested in cinema recognise the value of cinema exhibitors as an integral part of a broader, accessible, and inclusive cultural ecosystem, as well as a key component of contemporary urban development. In this regard, the Netherlands is often cited as an example of a vibrant cinema landscape, supported by financial and logistical assistance to local film houses and theatres.

A focus on ‘city cinemas’

Over the past four decades, large multiplexes have been built worldwide. Typically, they were constructed in an industrial style on the outskirts of cities, bypassing city centres for various reasons. This left inner cities to house different types of smaller cinemas, many of which have a long history in film exhibition.

New projects for smaller city cinemas were much rarer, probably because they were difficult to finance and operate on a financially sustainable basis. The films they screened were often more cultural and less commercial titles, which also made their offerings less profitable.

This case study focuses on Lumière Mechelen and delves into the delicate process of conceiving and building this kind of city cinema in a city center, in partnership with a bank and a city council.

Lumière Mechelen is not an isolated case. There are many more examples, notably across Europe, of new cinemas housed in heritage or historical buildings. They all focus on quality, both in their programming and in the overall experience. Additionally, each venue features a café (or restaurant) inside the building

A focus on Lumière Mechelen

The aim of this case study is to reconstruct the genesis of Lumière Mechelen in all its aspects, based on internal and external documents and interviews with most of the important participants in the process. Our analysis focused on mapping different factors contributing to creating the required context for sustainable small-scale theatrical exhibition in Europe.

This case study offers a reconstruction and reflection on a project initiated by the Lumière company. It draws on a wide range of sources, including:

Internal Lumière company documents (notes, letters, emails, reports, financial plans).

External communications from Lumière about the project (presentations, correspondence, funding applications, contracts).

Internal documents from the city of Mechelen (council reports, draft decisions, contracts, steering group notes).

Press coverage from various media outlets.

Content from relevant websites (cinemas, film fund, city of Mechelen).

Interviews with key stakeholders involved in the project, including city officials, the mayor and aldermen, brewery management, the architect, bank manager, and members of the Lumière team.

Lumière Mechelen, sketch by Lennart Claeys, photo archive Lumière

Case Study Lumière Mechelen

Lumière between past and future

The origins of Lumière go back to 1996 and the creation of a small cultural cinema by Jan De Clercq and Alexander Vandeputte in Bruges. Later, Lumière expanded its activities to film production and distribution. It became an important DVD publisher and film distributor and developed its own VOD platform.

In 2014, Lumière reopened Cinema Cartoon’s in Antwerp (after its bankruptcy), in 2019, it created a second arthouse movie theatre in Antwerp: Cinema Lumière Antwerp. In the same period, Lumière developed a new cinema location in the old city festival hall in Mechelen.

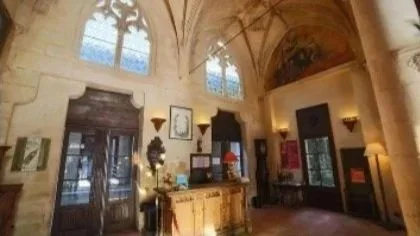

The historical building had to undergo an extensive renovation. Three cinemas were incorporated into a cinema tower that is constructed within the volume of the old city festival hall. Next to the cinema, there is also a cinema café called LUX28. Lumière Mechelen opened on October 7, 2021.

“When all cinemas had left the city, that was felt as a sign for the people of Mechelen that things were going badly for our city. Now the cinema is back in the city, now things are going well for Mechelen again.”

— Bart Somers (Mayor of Mechelen - opening speech)

In 2025, Lumière took over Cinema Focus in Geraardsbergen. For the first time, a more commercial cinema joined the Lumière group. Still a city cinema at heart, but located in a smaller city which requires greater attention to blockbusters and family entertainment.

While Lumière Mechelen is their most ambitious project to date, Lumière’s search for new locations, new take-overs and development projects is still ongoing.

The city cinema concept, as defined by Lumière

‘City cinema’ is a concept coined by Lumière’s founders, Jan De Clercq and Alexander Vandeputte. This concept revolves around the notions of urban setting, quality, love for cinema, and social and cultural added value.

Lumière Mechelen, photo archive Lumière

The project envisions a cinema that is well integrated into the urban fabric, designed to serve a broad audience of film and culture enthusiasts. It treats cinema not merely as entertainment but as a cultural experience, aiming to elevate film-going through thoughtful programming and presentation.

A contemporary film selection

The selection focuses on current cinema, with an emphasis on auteur films, particularly from Flemish and more generally European filmmakers. It prioritises artistically and socially relevant works, often less commercially driven. These films are given time and space to reach their audiences, with a constant search for cinematic gems that reflect cultural ambition over mass-market appeal.

Cinema in a high-quality context

The cinema offers a premium viewing experience with advanced projection technology and comfortable, crisp-free auditoria. Visitors can enjoy drinks rather than snacks, and the programming includes an enriched thematic offer, event screenings, and previews with guest talents, creating an environment where the cinema acts as both venue and curator.

A quality film experience

The experience begins before entering the screening room. The cinema aims for a distinctive, personable identity and fosters loyal relationships with its audience. Often accompanied by a café, it becomes a cultural hub within the city

Where cultural and economic objectives meet

A city cinema contributes both socially and culturally, while also playing a key economic role in the film distribution landscape. It combines cultural intent with economic viability, driven by the central question: “How can we reach the largest possible audience with beautiful films?”

Prime factors for success: location and infrastructure

Lumière Mechelen is not located in a typical cinema architecture, but in a prestigious historical building: the old city festival hall. In the case study, we distinguish the important features of this project, the important steps in the process, potential pitfalls, and opportunities that could enable future-proofness of similar upcoming projects.

“The argument of creating a local economy around this new arthouse cinema was, in terms of urban development, very important.” – Björn Siffer (Alderman of Culture of the city of Mechelen)

Cinema Lumière Mechelen opened in 2021 as part of an urban redevelopment project in collaboration with the City of Mechelen. It is located in the historic city centre, just 250 meters from the main square. Housed in the former city festival hall, it is reimagined as a vertical cinema tower with three stacked cinemas and 247 seats. The building features a blend of film and hospitality, with beverages & snacks offered in the surrounding galleries. State-of-the-art equipment and technology are indispensable.

“The café is not just catering. It’s part of the cinematic experience.” — Hans Rubens (Commercial Director, City Brewery Het Anker)

Lumière Mechelen, © Michiel De Cleene

The building

The historical building in which the cinema is located is dedicated to cinema, while at the same time its historic identity is respected. Next to the three cinemas, the presence of a cinema café is essential to complete the audience experience. The combination of the three elements makes Cinema Lumière Mechelen an appealing site.

Technological infrastructure

Each cinema is equipped with a state-of-the-art digital 2K projector and cinema server. Screens 2 and 3 have 5.1 digital sound, Screen 1 has a 7.1 digital sound system. A powerful ventilation, filtering, and heating unit is an important element of the cinema’s technical equipment. Especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, regulations concerning air quality became much more strict.

A unique collaboration and active support from the city

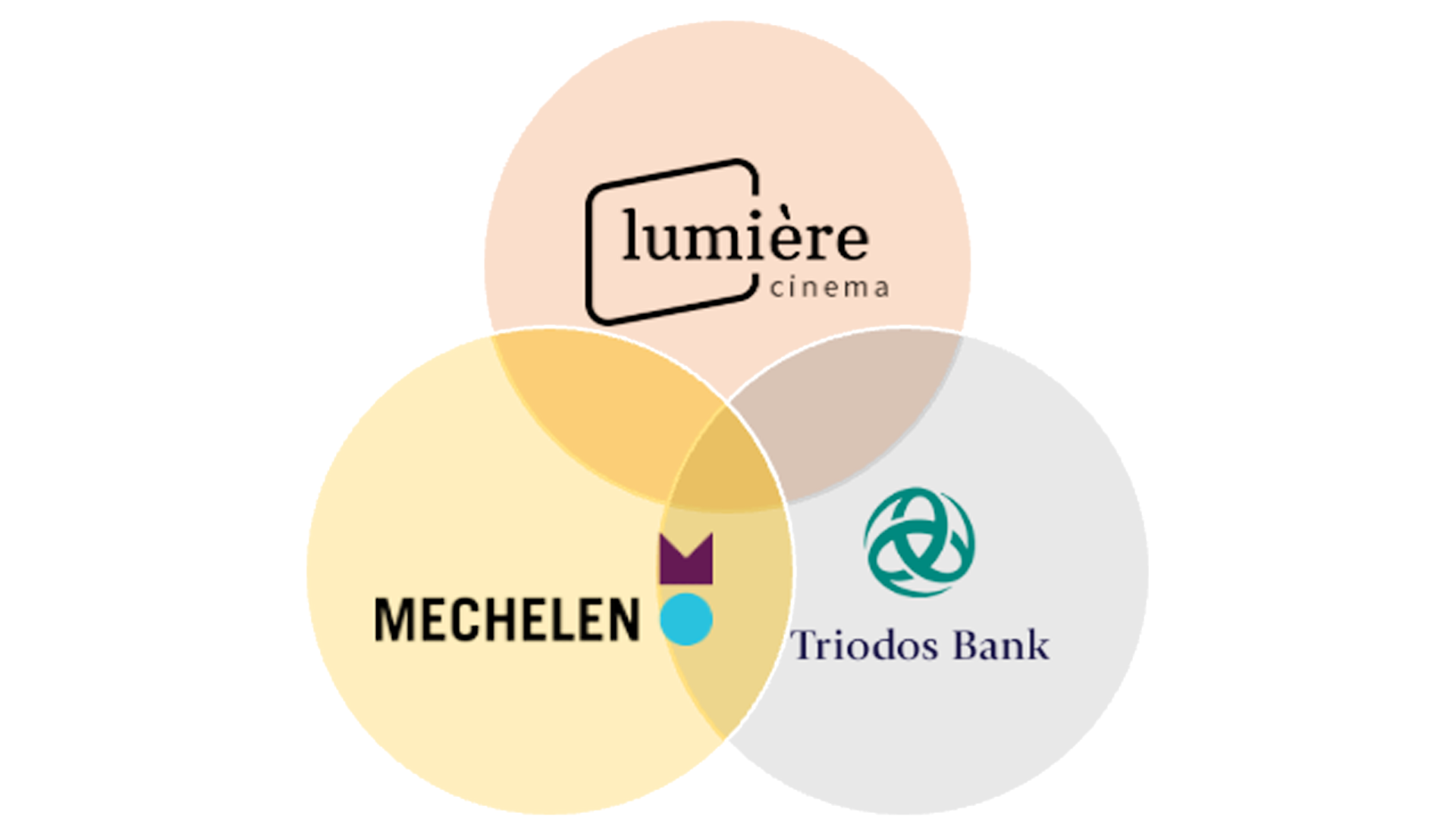

The triangle exhibitor-city-bank

For Lumière Mechelen, the unique collaboration between the exhibitor, the city council, and a bank with a shared focus on added value was vital to the success.

In the case of major renovation works, such as in Mechelen, financial support from the local government is necessary to make the project possible. Next to an important financial investment in the renovation of the building, Lumière obtained from the city a leasehold agreement for a period of 27 years.

“We considered those financial means as an investment, and not really as a subsidy.” - Björn Siffer (Alderman of Culture of the city of Mechelen)

To finance the remaining cost of the project, Lumière was able to convince Triodos Bank for a loan with the leasehold rights as collateral.

“A leasehold is a workable model if the city wants to activate cultural infrastructure.” - Béatrice Gilmont (Relationship Manager at Triodos Bank)

The two partnerships are based on sound financial agreements, but also on a shared belief in the value of the social benefits of the project.

"A tradition continues to exist. It has been brought back to life with an incredible amount of respect for the value of this monument. This is Mechelen at its most beautiful. Being proud of our history, cherishing the past, but also daring to build a new future.” — Bart Somers (Mayor of Mechelen)

A business plan

Five key elements define Lumière Mechelen’s business plan:

The leasehold agreement with the city: Thanks to a 27-year leasehold agreement with the city council, locating the cinema in the Mechelen city centre became financially feasible.

The city council’s contribution: The city of Mechelen invested heavily in the renovation of the building.

A tight HR concept: Staffing is very tight with only 2 Full Time Equivalent (FTE), supplemented with student workers.

Advantages of scale: Cinema Lumière Mechelen is part of a group of cinemas. Part of the workload is taken care of by a team at the head office in Ghent (programming, technical issues, etc.).

Being part of the film industry’s value chain: Lumière is against freewheeling practices which benefit one actor, but are harmful for the industry as a whole. Lumière insists on professional ethics.

Lumière Mechelen, © Michiel De Cleene

Audience expectations (60,000/year) were immediately met in 2022 and were largely exceeded in 2023. People in Mechelen were enthusiastic about Lumière Mechelen. This, even though COVID-19 still had a major impact on visitor figures in 2022, and Lumière Mechelen opened in the most difficult period for cinema in recent history. There is a positive vibe among young and old visitors, also among.

The cinema has an excellent location. People come to Lumière Mechelen because they enjoy spending time in an inspiring building in the city centre.

Attention for film titles for a wide audience is appreciated by the city. Compared to the other Lumière locations, the crossover titles in the programming in Mechelen attract the largest audience. The classic arthouse titles are having a slightly more difficult time there than at the other locations. Building an arthouse audience inevitably takes time.

For the city council, Lumière Mechelen is in the first place, a project of urban renewal. The cultural objectives come second.

Lumière Mechelen is a location where many events take place. More than in other Lumière locations, undoubtedly because of its inviting and appealing nature. Cinema and other professionals like to use the theatre for events: avant-premieres, B2B events, the ‘CINEMAS’ festival (in collaboration with Sphinx Ghent and Budascoop Kortrijk), etc.

The building wears out faster than expected. Carpets, seats, etc. bear signs of the cinema’s success and involve additional cost.

Technical equipment goes beyond cinema equipment. Other technicalities require attention. Ventilation is often a critical issue, especially after the new COVID-19 regulations. In Mechelen, it was only two years after the opening that a technical error causing the ventilation to work poorly was discovered and repaired.

Achieving synchronicity between the cinema and the café can be challenging, especially when an external operator is involved. Outsourcing the café is likely no longer a viable option. Given the tight business model of the city cinema, the café has become an ideal partner and a strategic means to increase profit margins and generate additional income for future investments.

At the most conceptual level of the project, an intuitive agreement between the different parties was reached quickly. However, this may have led to a situation where the project’s objectives were not always fully articulated, resulting in struggles at a lower level during decision-making.